19 Aug 2019

1 CommentJames Gillray

James Gillray was a contemporary of Thomas Rowlandson, and he could be every bit as biting in his representations of medicine. For example, in 1801 he satirized the craze from the US to Britain for Perkin’s Tractors, a device whose “inventor,” Elisha Perkins, claimed it cured all manner of disease through electric force.

Gillray skewers the outlandish claims made on behalf of the device, evidenced by the newspaper open on the table of the unfortunate patient: “Just arrived from America … Perkinism in all its Glory,—being a certain Cure for all Disorders: Red Noses, Gouty Toes, Windy Bowels, Broken Legs, Hump Backs.” An adjacent headline announces an equally plausible discovery: “Just discover’d the Grand Secret of the Philosopher’s Stone with the True way of turning all Metals into Gold.” The claims in Gillray’s satire, however, were somewhat modest compared to those offered by Perkins’ son, Benjamin, who brought the devices to London. The tractors, Perkins claimed in his promotional material, “have been found a safe, speedy, and effectual Remedy of the following Disorders. Acute and Chronic Rheumatism, including Lumbago and Sciatica, Gout, Sprains, Contusions, Scalds, Inflammations of the Eyes; also of the Skin, … Painful Flammatatory Tumours, as Biles and Whitlows; Violent Spasmodic Convulsions; as Epileptic Fits, Cramp and Locked Jaw; Pleurisy; Stings and Venemous Insects…” and so on, ending with a promise of similar cures for “all analogous Diseases of Horses.”

Two Perkins ‘tractors’. Science Museum Group Collection Online. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co140928.

Of course, Gillray’s satire of Perkin’s tractors and its absurd claims are only part of his satire. He is if anything more amused by the patient himself, a man who has clearly brought on his ailments through the steady consumption of the brandy, wine, and pipe in his table (and the painting above his head suggests a general career in overindulgence). Indeed, as much as Gillray shared his contemporary’s love of needling physicians and their empty promises, in his medical cartoons he often focused more on the patient than the medical caregiver.

In the Drawing Blood exhibit at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, we featured Gillray’s Gentle Emetic, one of a series he executed focusing on the experience of being a patient in the age before modern medicine:

Here the caregiver holds the patient’s head above the bowl while the two wait for the emetic to do its work. Along other draining treatments such as bleeding, sweating, and laxative purgation, medically-induced vomiting was understood to be cleansing and therapeutic. The painful experience of undergoing such treatment is made clear by the agony displayed on the patient’s face and the contortions of his hands.

The most notorious of the treatments from the age of heroic medicine is bloodletting, a practice represented in Gillray’s Breathing a Vein. Here a lancet (or a multi-bladed scarificator) cuts the vein and the patient is bled into a bowl to a prescribed level. In Gillray’s cartoon, the patient looks away from his wound, growing pale and faint as his blood pressure drops. The physician, meanwhile, anxiously watches the patient: with no tool yet available to monitor blood pressure or other vital signs that might provide warning of complications from the procedure, only attendance to the patient’s visible symptoms will let him know if things are about to take a dire turn. Once the proper amount of blood is removed from the body, the tourniquet is removed and the wound is closed to stop the bleeding. But of course it was not always possible to stop the bleeding in time to prevent the patient from passing out or even expiring from hypotension and shock.

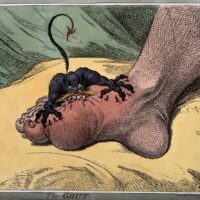

Together, these two images provide a modern viewer with a sense of what it would have felt like to be a patient in the age of “heroic medicine.” Indeed, these two cartoons also suggest why why patients were willing to take the financial risk on quack remedies such as Perkins’ Tractors. And of course, The Gout, arguably Gillray’s most famous medical cartoon, reminds us of the pains of everyday ailments that led people to submit themselves to such treatments—heroic and quack—in the first place. Pain was everywhere and there were precious few reliable or safe remedies.

Of course, as the Gillray cartoon below on the right suggests, these is always punch: to paraphrase Homer Simpson, the cause and the solution to all of life’s problems. “Punch Cures the Gout, the Colic and the ‘Tisick” (the latter referencing consumption, thus the gaunt appearance of the third gentleman)—the traditional rhyme concluding “and is by all agreed the very best of Phisick.”

Jared Gardner is a professor and patient at the Ohio State University.

Student Post: Drawing Blood by Emily Winter | Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum Blog

February 25, 2020 @ 6:50 pm

[…] They bear a striking resemblance, don’t they? Indeed, the British Caricaturist and Printmaker James Gillray, author of the cartoon titled The Gout, was a major influence on Cruikshank’s art. One can see […]