5 Apr 2020

4 CommentsThe Spanish Flu in Comics Strips, 1918

This is the first of a series of posts about comics and the Spanish Flu pandemic. In our second installment we will look at editorial cartoons about the flu and the attempts to visualize the viral “enemy.”

It used to be hard for us to grasp how devastating was the H1N1 pandemic of 1918-20, although as I write these words is becoming easier every day. We live with the flu as one of our annual seasonal viruses, and today we have at our disposal both flu vaccines and antibiotics to manage the secondary complications the flu can leave in its wake. In 1918, neither was available. However, that alone does not account for the fact that this particular strain of influenza killed up to 5% of the world population—roughly 50 million by most estimates. While in normal years, influenza kills several thousand in the U.S. each year, its victims are disproportionately the very old, the very young, and the immune-compromised. That was not the case with the Spanish Flu, and the specter of another such influenza haunts epidemiologists and public health officials every flu season. The arrival of COVID-19 suggests how unprepared we are.

In looking at cartoons related to the Spanish Flu from a century ago, it is at first surprising how relatively few there were during the first months of the disease, beginning in March 1918. Of course, much of the world was mired in a world war, and the growing number of deaths at home front did not register as prominently as did news from the front. In addition, wartime meant that news was controlled by state censors. For the U.S. military, the influenza and secondary pneumonia hit 20-40% of personnel, a huge blow to military effectiveness and not one that they wanted to share with the world.[1] And the growing number of deaths at home would serve only to dampen morale of soldiers shipping overseas. As a result news of the full impact of the flu was not fully understood until war’s end, and the majority of the earliest comic strips addressing the pandemic appeared late in the war as peace became increasingly inevitable.

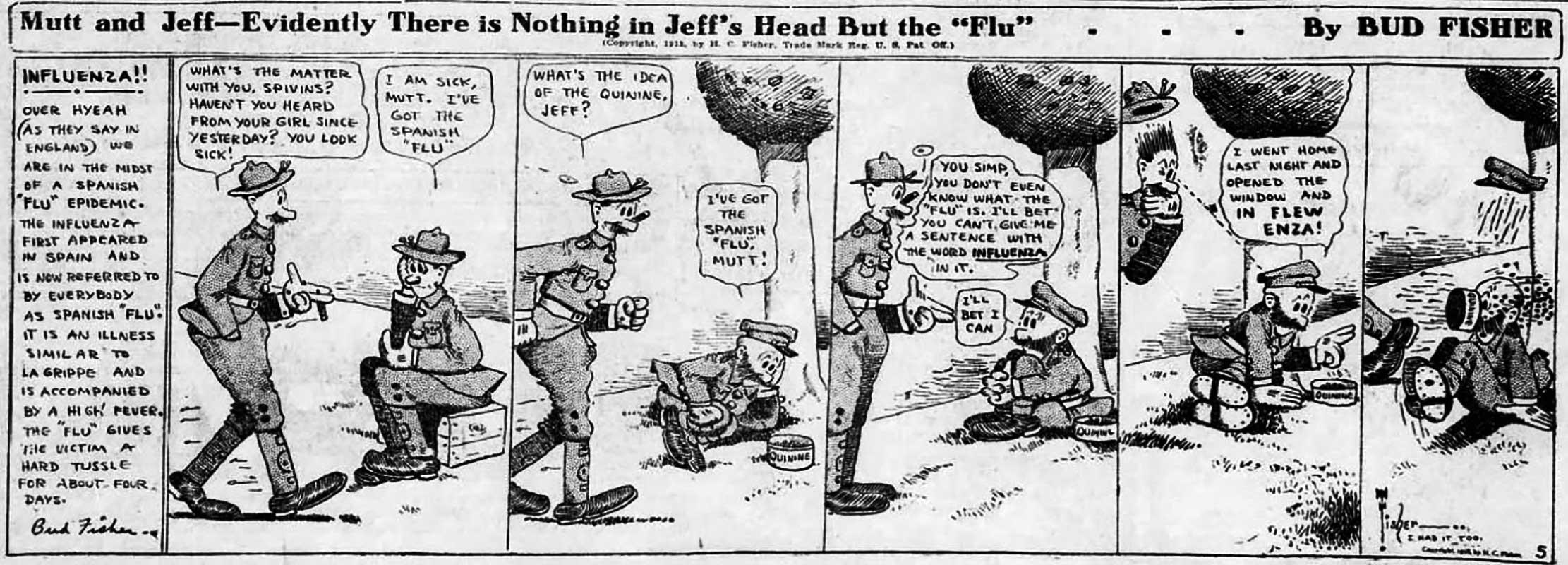

Here for example is August 13 installment of Mutt and Jeff:

It makes sense that Bud Fisher’s Mutt & Jeff was among the first American comic strips to directly reference the Spanish Flu epidemic. Fisher had been engaging with the news—first the sports page and later the headlines—since he launched the strip in 1907, and this formula helped create the first successful daily newspaper comic strip. It is also not surprising that the topic arises here in relation to a military camp, since these settings were among those most severely impacted by the pandemic. But the seriousness of the virus for soldiers at home and abroad is not of course the topic of the strip, which instead focuses on what was already becoming a familiar joke: “In flew Enza.”

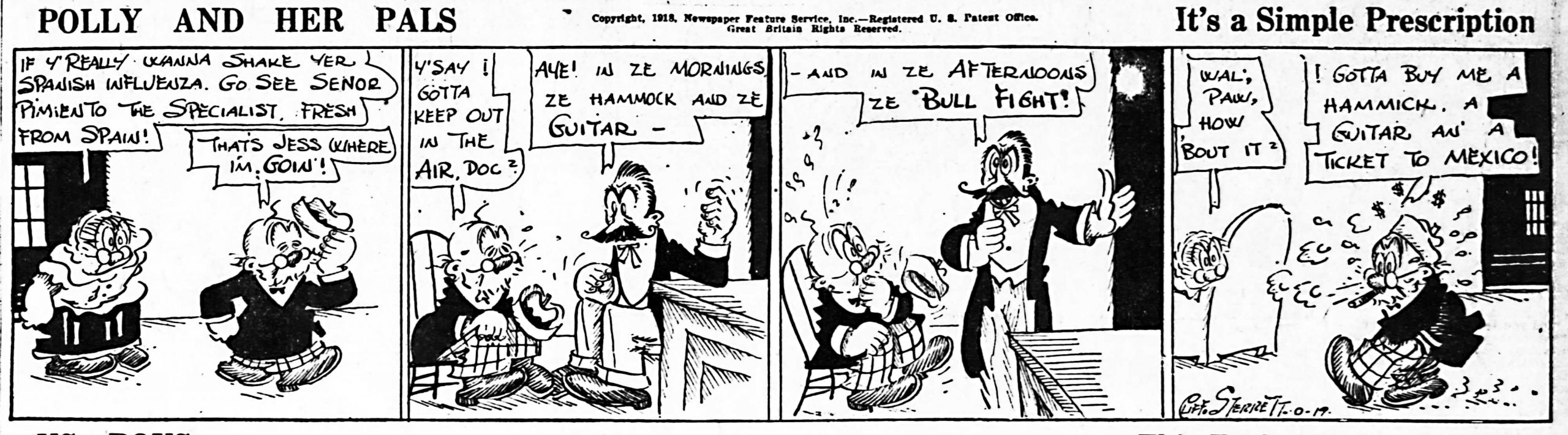

Other comic strips from the period made reference to the flu, a sign of its impact on the American imagination given that most daily “funnies” avoided engagement with unpleasant topical affairs. Many characters would come down with the virus during the course of 1918, including Paw Perkins from Polly & Her Pals by Cliff Sterrett:

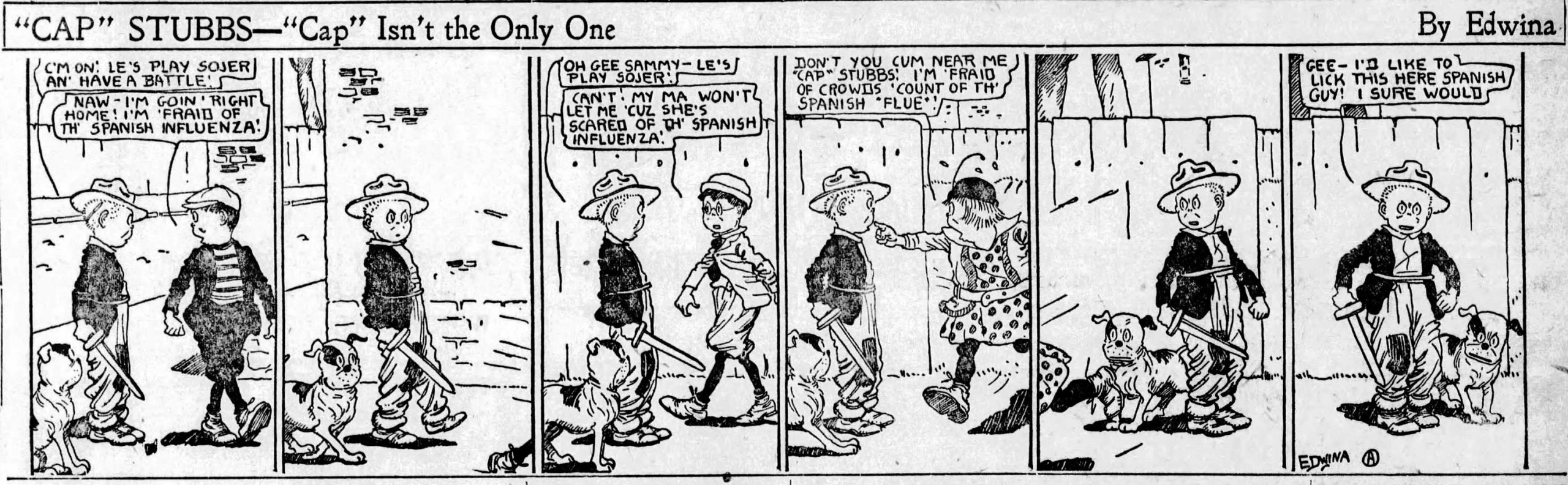

That Edwina Dumm tackled the impact of the flu on daily life made sense, given that she had begun her career as an editorial cartoonist—the first woman employed in the role in the U.S.—at the Columbus Monitor in 1915. When the Monitor folded in 1917, she moved to New York and created her first syndicate strip, eventually named Cap Stubbs and Tippie, about a boy and his dog. In the 1918 installment below, Cap struggles to find a playmate, as the Spanish flu had forced all kids to avoid crowds of any kind:

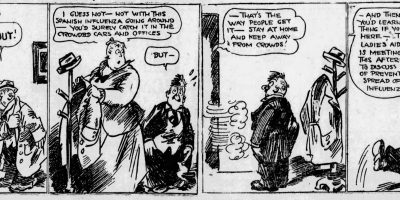

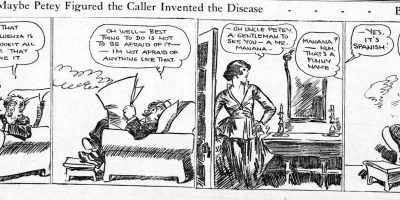

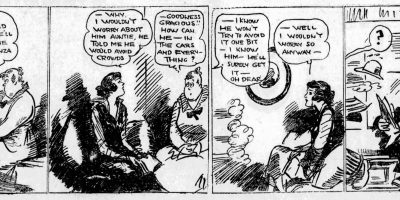

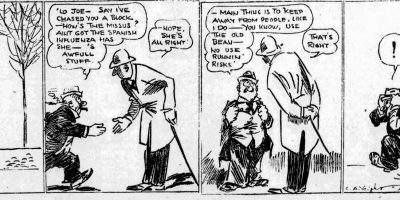

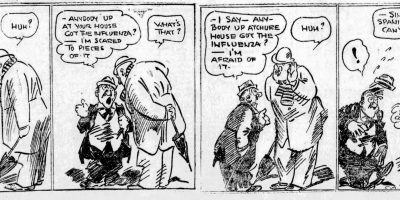

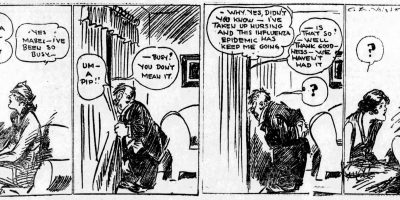

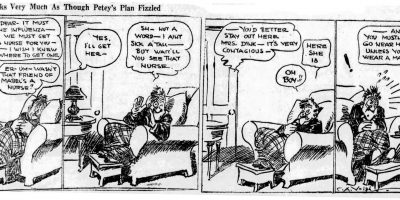

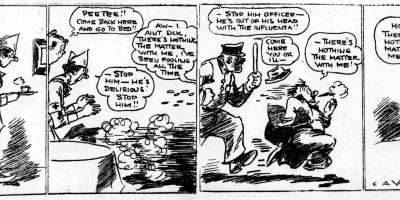

Charles Voigt’s first strip, Petey (or Petey Dink) had recurring fun with the topic of Spanish flu over the course of almost two weeks in October:

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 15, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 16, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 17, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 18, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 19, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 21, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 22, 1918

- Charles A. Voigt, Petey Dink, October 24, 1918

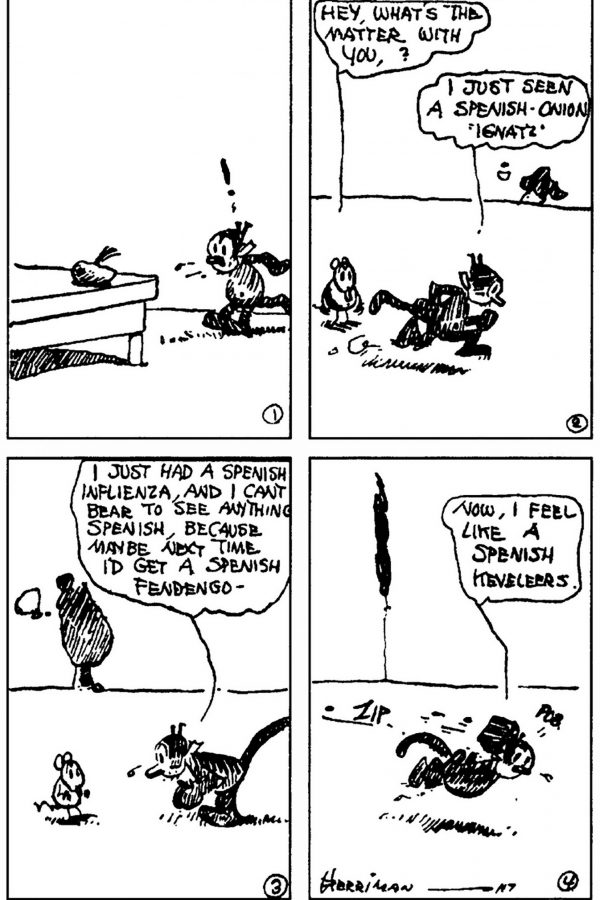

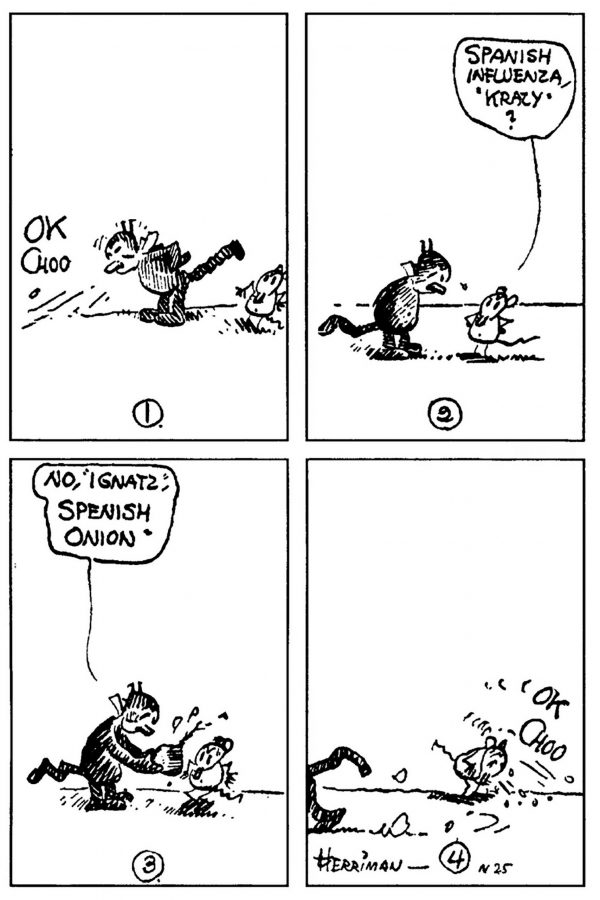

My personal favorite shout-out to the pandemic from 1918 comes from my favorite comic strip of all time, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, telling the tale of one of the more bizarre lovers-triangles ever conceived—between a brick-throwing mouse, a mouse-loving cat, and a cat-loving canine officer of the law—for over thirty years. In the installments below, two daily strips and one glorious Sunday, we see how Herriman took seriously both the disease and its social consequences even as he took immense pleasure in teasing an alternative etiology for the virus.

- George Herriman, Krazy Kat , November 7, 1918

- George Herriman, Krazy Kat , November 25, 1918

What we see in the newspaper comic strips during the first devastating year of the pandemic is a desire to use humor both to provide comfort and ameliorate fear, but also to educate. Petey Dink and “Cap” Stubbs both spell out the need for what today we call social distancing and the dangers of transmission in crowds and through casual socializing. Polly and Her Pals ridicules the phony “cures” and hucksters who prey on all such crises, then as now. Mutt and Jeff highlights the unique challenges facing the military during the pandemic of 1918 (and indeed, armed forces in our own pandemic face increased risks as well). Finally, Krazy Kat, written by the first cartoonist of color—and one who lived his public life passing as White—reminds us of the dangers of xenophobia as the media and public imagination associates the supposed country of “origin” for the pandemic with disease and contagion. And in the Sunday page from September, we see a fairly potent reminder of the disruptions the disease presents to the normal course of life, as both Krazy and Ignatz take to their separate beds and not a brick is thrown.

[1] See Carol R. Byerly, “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919,” Public Health Report 125 (2010 ): 82–91.

Jared Gardner is a professor and patient at the Ohio State University.

April 6, 2020 @ 11:03 pm

Poor Edwina is still getting her name misspelled. You got it right in some places, but not at the top of paragraph 5: “That Edwina Dumb tackled the impact of the flu…”

April 7, 2020 @ 1:05 am

Argh! I hate autocorrect! Fixed now: thanks for the catch

April 6, 2020 @ 11:11 pm

Otherwise, good article!

November 16, 2020 @ 10:33 pm

The Outbursts of Everett True has three great strips on Spanish Flu.

https://imgur.com/gallery/70a1SXU